Don’t Forget Your Beans - Kidney Disease

Don't Forget Your Beans

CKD Stage III with Albuminuria — The Cardiometabolic Orphan

Case Presentation

Maria is 58 years old. She has type 2 diabetes, managed with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Her last hemoglobin A1c was 7.8%. She takes lisinopril 20 mg and amlodipine 10 mg for hypertension. Her BMI is 34. She has been told to "lose some weight" at every visit for the last decade.

Her primary care doctor ordered routine labs and noticed her creatinine was 1.3 mg/dL. Her estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated to 48 mL/min/1.73m². A urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) came back at 180 mg/g. She was referred to nephrology.

The nephrologist reviewed her labs, noted she was "Stage IIIb, A2," and said: "Your kidneys are holding steady. We'll recheck in six months. Make sure you stay hydrated and keep your blood pressure controlled."

Meanwhile, Maria had been experiencing exertional shortness of breath. Her cardiologist ordered a stress echocardiogram — mildly abnormal. A coronary CTA showed scattered non-obstructive plaque. "No significant blockages," her cardiologist told her. "Your heart looks okay."

What nobody told Maria:

Her eGFR of 48 with a UACR of 180 mg/g — CKD Stage IIIb with moderately increased albuminuria — places her in a "high risk" category on the KDIGO heat map. Multiple landmark studies — including Go et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine and the Writing Group for the CKD Prognosis Consortium (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, Albuminuria, and Adverse Outcomes: An Individual-Participant Data Meta-Analysis) — suggest her cardiovascular risk is comparable to someone who has already had a heart attack.

Nobody started an SGLT2 inhibitor — a drug class now shown in the DAPA-CKD, EMPA-KIDNEY, and CREDENCE trials to simultaneously protect the kidneys, reduce heart failure hospitalizations, and lower cardiovascular death.

Nobody discussed finerenone — a newer nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist specifically shown in the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials to reduce both kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD with albuminuria.

Her lisinopril was never titrated to maximum dose. Nobody checked an ApoB to see if her lipid management was truly adequate. Nobody mentioned a GLP-1 receptor agonist, which now has dedicated kidney outcome data from the FLOW trial. Her nephrologist and cardiologist had never spoken to each other.

Maria fell into the gap. She is not alone.

Flying Under the Radar

CKD Stage III with albuminuria is one of the most common and most consequential conditions in modern cardiometabolic medicine. And yet it consistently falls through the cracks — not because the evidence is lacking, but because of how our healthcare system is organized.

"Not Bad Enough for Nephrology, Not Sexy Enough for Cardiology"

CKD Stage III (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73m²) is the most commonly diagnosed stage of chronic kidney disease.

- Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease — A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease in adults, 1990–2023, and its attributable risk factors: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023 - The Lancet

An estimated 12–15% of U.S. adults have some form of CKD, and many of them have never been told.

- VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Primary Care Management of Chronic Kidney Disease

- Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management: A Review

Stage III is often discovered incidentally on routine labs. The word "chronic" sounds stable. The word "stage III" sounds like it's in the middle — not urgent. And so it gets watched, not treated.

ASCVD Risk Is Systematically Underappreciated

The 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines list CKD as a "risk-enhancing factor" for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Many international guidelines and experts go further, considering CKD Stage III with albuminuria to be a coronary heart disease risk equivalent — meaning these patients should be treated with the same intensity as someone who has already had a heart attack. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association reinforces that even moderate reductions in eGFR, and especially the presence of albuminuria, confer independent, graded cardiovascular risk that is often not reflected in standard risk calculators.

The Pooled Cohort Equations used to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk do not directly incorporate eGFR or albuminuria. That means a patient like Maria — whose risk is substantially higher than the calculator suggests — may be told her risk is "borderline" when it is anything but.

Albuminuria: Checked Rarely, Trended Even Less

Albuminuria is one of the most powerful predictors of both kidney disease progression and cardiovascular events. Yet in clinical practice, UACR is frequently not ordered. When it is, it is often a one-time check that is never repeated. The KDIGO 2024 guidelines recommend checking UACR at least annually in all patients with CKD, diabetes, or hypertension. In practice, this happens far less often than it should.

The Specialty Gap

Perhaps the most insidious reason CKD III with albuminuria flies under the radar is the gap between specialties. Cardiologists focus on coronary arteries, valves, and arrhythmias. When they see a creatinine on a lab panel, many will note it and defer to nephrology. Nephrologists, meanwhile, are often focused on electrolyte management, dialysis access, and transplant evaluation. They may not feel comfortable prescribing high-intensity statins, optimizing lipid therapy with ApoB targets, or initiating agents primarily viewed as cardiovascular drugs.

SGLT2 inhibitors were initially approved as diabetes medications. Then they became heart failure drugs. Only recently have they been broadly recognized as kidney-protective agents that also reduce cardiovascular events. Finerenone is newer still — many cardiologists have never prescribed it. The result: a patient with CKD III and albuminuria may see three specialists and still not receive the therapies that the evidence says she needs.

CardioAdvocate Checklist

These are the questions and assessments that should be part of every encounter for a patient with CKD Stage III and albuminuria. Print this. Bring it to your visit.

Deep Dive

This section is a living, evolving knowledge layer. It covers pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, controversies, and the emerging evidence base for managing CKD Stage III with albuminuria as a cardiometabolic disease.

What CKD Stage III Really Means

Chronic kidney disease is classified by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) organization based on two independent axes: eGFR (a measure of how well the kidneys filter) and albuminuria (a measure of protein leaking into the urine). Stage III means the eGFR is between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73m² and is further subdivided into Stage IIIa (45–59) and Stage IIIb (30–44).

Albuminuria is categorized by the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR): A1 is normal to mildly increased (< 30 mg/g), A2 is moderately increased (30–300 mg/g), and A3 is severely increased (> 300 mg/g).

The KDIGO heat map KDIGO Digital Heat Map combines these two axes into a color-coded risk grid. The risk is not additive — it is multiplicative. A patient with Stage IIIa and A2 albuminuria is at high risk. A patient with Stage IIIb and A2 is also at high risk trending toward very high risk. This is where Maria sits.

KDIGO Heat Map: CKD Risk Stratification by eGFR and Albuminuria

| Stage | eGFR (mL/min/1.73m²) |

A1 (< 30 mg/g) |

A2 (30–300 mg/g) |

A3 (> 300 mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | ≥ 90 | Low risk | Moderately increased | High risk |

| G2 | 60–89 | Low risk | Moderately increased | High risk |

| G3a | 45–59 | Moderately increased | High risk | Very high risk |

| G3b | 30–44 | High risk | Very high risk ← Maria | Very high risk |

| G4 | 15–29 | Very high risk | Very high risk | Very high risk |

| G5 | < 15 | Very high risk | Very high risk | Very high risk |

Source: Adapted from KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for Chronic Kidney Disease. Colors indicate risk of CKD progression and cardiovascular events.

Albuminuria: More Than a Kidney Marker

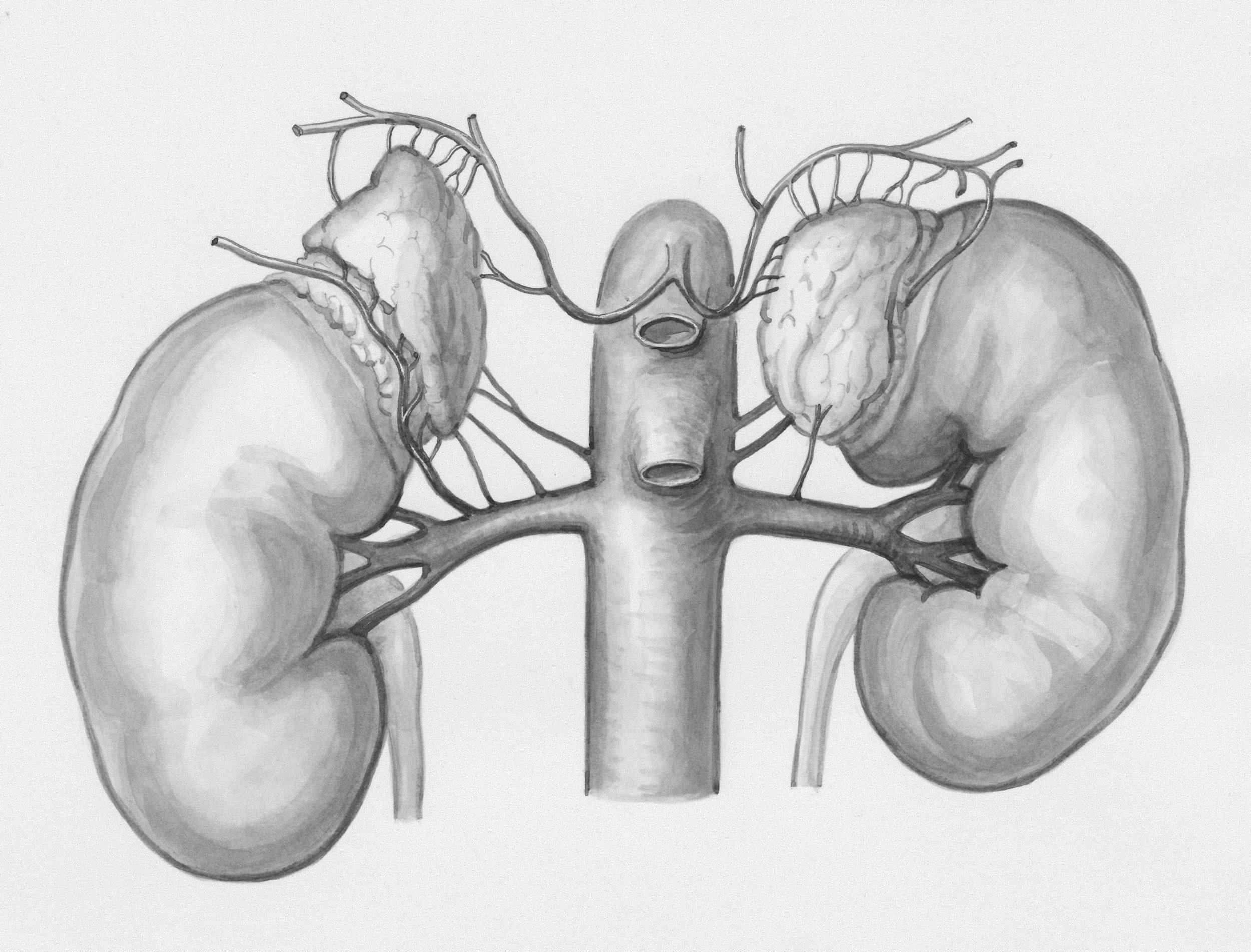

Albuminuria is often discussed as if it were exclusively a nephrology problem. It is not. When albumin leaks through the glomerular filtration barrier, it is a signal of endothelial dysfunction — and that dysfunction is not limited to the kidney. It is systemic.

The glomerulus is a microvascular bed. When its endothelium is damaged by hypertension, hyperglycemia, inflammation, or other metabolic insults, albumin crosses the barrier into the urine. But the same endothelial injury is occurring simultaneously in the coronary arteries, the cerebral vasculature, and the peripheral circulation. Albuminuria is, in essence, a urinary biomarker of vascular disease happening everywhere.

The landmark 2010 meta-analysis by the CKD Prognosis Consortium (Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis) of over 1.1 million participants, demonstrated that both reduced eGFR and increased albuminuria independently predict all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and kidney failure. The risks were multiplicative: patients with both low eGFR and high albuminuria faced dramatically higher risk than those with either alone.

Data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and this meta-analysis (Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data) have consistently reinforced these findings. Albuminuria predicts cardiovascular events even when eGFR is still relatively preserved, making it an early warning signal that is tragically underutilized.

CKD as an ASCVD Risk Enhancer — The Evidence

In 2004, Go and colleagues published a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine examining over 1.1 million adults in the Kaiser Permanente system. They demonstrated a graded, independent association between reduced eGFR and the risk of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. Patients with an eGFR of 45–59 had a hazard ratio for cardiovascular events of approximately 1.4 compared to those with normal kidney function. At eGFR 30–44, the hazard ratio rose to approximately 2.0. These risks persisted after adjusting for age, sex, race, comorbidities, and albuminuria.

The 2003 AHA Scientific Statement was among the first to formally argue that CKD should be considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent — analogous to diabetes. They pointed out that patients with CKD are far more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than to progress to dialysis. This remains true today (2023 AHA CKM Scientific Statement).

In 2012, Tonelli et al., (Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort study) published a population-based cohort study comparing cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD versus those with diabetes. They found that CKD conferred a level of coronary event risk comparable to diabetes — and that patients with both CKD and diabetes had the highest risk of all.

Despite this evidence, the standard ASCVD risk calculators (Pooled Cohort Equations) used in the 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines do not directly incorporate eGFR or albuminuria. CKD is listed as a "risk-enhancing factor" that can tip clinical decisions — for example, favoring statin initiation in a patient whose calculated risk is borderline. But in practice, this nuance is often missed. Clinicians see a 10-year risk estimate of 8% and feel reassured, not recognizing that the patient's true risk may be 15–20% or higher when CKD is factored in.

The Cardiorenal-Metabolic Syndrome: Everything Connects

In 2023, the American Heart Association published a Presidential Advisory formally defining Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome as a systemic disorder arising from the pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. This was a watershed moment: for the first time, a major medical society formally acknowledged that these diseases are not independent — they are interconnected at every level.

The pathophysiology is bidirectional and self-reinforcing. Obesity drives insulin resistance, which promotes hyperglycemia and hypertension. Hyperglycemia damages the glomerular endothelium, causing albuminuria. Albuminuria signals systemic endothelial dysfunction, which accelerates atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis stiffens the arterial tree, raising afterload on the heart. The heart remodels, developing diastolic dysfunction (the precursor to HFpEF). Heart failure causes venous congestion, which directly worsens kidney function. Worsening kidney function impairs sodium and water excretion, which worsens congestion and hypertension. And so the cycle feeds itself.

This is not a linear sequence. It is a web. And at the center of this web, for many patients, sits CKD Stage III with albuminuria — the marker that something has gone wrong systemically, and the signal that intervention is most needed.

The Cardiorenal syndrome (originally classified by Ronco et al.) describes the bidirectional relationship between heart and kidney failure. Type 1 (acute cardiorenal) and Type 2 (chronic cardiorenal) describe how heart failure damages the kidneys. Types 3 and 4 describe how kidney disease damages the heart. Type 5 encompasses systemic conditions (like diabetes or sepsis) that damage both simultaneously. CKD III with albuminuria in a patient with diabetes and obesity often represents Type 5 — a systemic metabolic assault on both organs.

CKD and Diabetes: The Deadly Partnership

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of CKD worldwide and the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease in the United States. But the relationship between diabetes and CKD extends far beyond simple glucose-mediated nephropathy.

Hyperglycemia promotes the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that damage the mesangial cells and podocytes of the glomerulus, leading to mesangial expansion, basement membrane thickening, and progressive albuminuria. But diabetes also drives CKD through hemodynamic mechanisms: insulin resistance increases tubular sodium reabsorption, reducing sodium delivery to the macula densa and activating tubuloglomerular feedback in a way that promotes glomerular hyperfiltration. This hyperfiltration — which may paradoxically manifest as a normal or high eGFR early in the disease — is itself damaging, accelerating glomerular injury over time.

What makes this partnership especially dangerous is that CKD worsens the metabolic derangements of diabetes. The failing kidney is a gluconeogenic organ — as kidney function declines, glucose metabolism changes unpredictably. Insulin clearance is reduced, increasing the risk of hypoglycemia. Drug dosing becomes more complex. And the chronic inflammatory state of CKD further worsens insulin resistance, creating a vicious cycle that De Fronzo and others have described as part of the "ominous octet" of metabolic dysfunction.

For the cardiologist, the critical point is this: a patient with diabetes and CKD is not simply a patient with two diseases. They are a patient with a single, interconnected syndrome in which the kidney disease amplifies the cardiovascular risk of diabetes, and the diabetes accelerates the progression of kidney disease. Treating one without treating the other is incomplete care. For more information on diabetes management as a cardiometabolic syndrome, see our article The Sweet Spot.

CKD and Heart Failure: The HFpEF Connection

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and CKD share a remarkable degree of overlap — in risk factors, pathophysiology, and outcomes. Both are driven by obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and aging. Both involve microvascular inflammation and fibrosis. Both are characterized by neurohormonal activation, particularly of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system.

The hemodynamic connection is direct. HFpEF causes elevated left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures, which transmit backward to the right heart and the venous system. This venous congestion increases renal venous pressure, directly reducing the glomerular filtration gradient and worsening kidney function — even when cardiac output is preserved. This is the "congestion hypothesis" of cardiorenal syndrome, and it explains why so many HFpEF patients develop worsening CKD over time.

Conversely, CKD promotes sodium and water retention, expanding plasma volume and worsening the hemodynamic burden on a heart that already struggles with diastolic filling. CKD also promotes arterial stiffness (through vascular calcification, medial hypertrophy, and loss of nitric oxide bioavailability), which raises afterload and further impairs diastolic relaxation.

The landmark EMPEROR-Preserved trial and the DELIVER trial demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular death in HFpEF — and subgroup analyses consistently showed benefit in patients with coexisting CKD. This means a single drug class can simultaneously address both conditions: protecting the heart from congestion-mediated injury and protecting the kidneys from hemodynamic and metabolic damage.

Cardiologists managing HFpEF should routinely screen for CKD (eGFR and UACR). Nephrologists managing CKD should screen for HFpEF (BNP or NT-proBNP, with echocardiography if abnormal). The failure to do so means that many patients with both conditions are being undertreated for each. For detailed exploration of HFpEF, see The Enigma HFpEF.

CKD and Obesity: The Adipose-Kidney-Heart Axis

Obesity is an independent risk factor for CKD, even in the absence of diabetes and hypertension. Obesity-related glomerulopathy is a recognized pathological entity characterized by glomerulomegaly and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. The mechanisms include direct compression of the renal parenchyma by visceral adipose tissue, increased metabolic demand leading to glomerular hyperfiltration, and a chronic inflammatory state mediated by adipokines (leptin, resistin, adiponectin, TNF-α, IL-6) secreted by dysfunctional adipose tissue.

The FLOW trial — a landmark randomized controlled trial of semaglutide (a GLP-1 receptor agonist) in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD — was stopped early for overwhelming efficacy. Semaglutide reduced the primary composite kidney outcome by 24% and showed significant reductions in cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality. While semaglutide was tested in patients with diabetes, the mechanisms of benefit likely extend beyond glucose control: weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation, and possibly direct tubular protective effects.

The SELECT trial demonstrated that semaglutide reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 20% in patients with obesity (without diabetes) and established cardiovascular disease. Pre-specified subgroup analyses are examining kidney outcomes in this population. The convergence of evidence from FLOW and SELECT suggests that addressing obesity with GLP-1 receptor agonists may protect the heart, kidneys, and metabolic system simultaneously.

For the clinician managing CKD III with albuminuria, obesity is not a cosmetic issue — it is a modifiable driver of kidney and cardiovascular disease. Weight management, whether through pharmacotherapy (GLP-1 RAs), lifestyle intervention, or bariatric surgery, should be a central part of the treatment plan.

The SGLT2 Inhibitor Revolution

No drug class has transformed cardiometabolic nephrology in the last decade as profoundly as the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Originally developed to lower blood glucose in type 2 diabetes, these agents have proven to be among the most effective therapies ever studied for kidney protection, heart failure prevention, and cardiovascular risk reduction — regardless of diabetes status.

The CREDENCE trial (2019) was the first dedicated kidney outcomes trial. Canagliflozin reduced the primary composite of end-stage kidney disease, doubling of serum creatinine, or renal/cardiovascular death by 30% in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD with albuminuria. The trial was stopped early for efficacy.

The DAPA-CKD trial (2020) expanded the evidence dramatically. Dapagliflozin reduced the primary composite kidney outcome by 39% in a broader population of CKD patients — and critically, the benefit was consistent in patients with and without diabetes. This was a paradigm shift: SGLT2 inhibitors were not just diabetes drugs that happened to help the kidneys. They were kidney drugs, period.

The EMPA-KIDNEY trial (2022) enrolled the broadest CKD population yet, including patients with eGFR as low as 20 and even patients without significant albuminuria. Empagliflozin reduced the primary outcome of kidney disease progression or cardiovascular death by 28%. Benefits were seen across the eGFR spectrum and in patients with diverse etiologies of CKD.

The mechanism of SGLT2 inhibitors in the kidney involves restoring tubuloglomerular feedback. By blocking sodium-glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule, these agents increase sodium delivery to the macula densa, triggering afferent arteriolar constriction and reducing the harmful glomerular hyperfiltration that drives progressive kidney injury. This produces a characteristic initial "dip" in eGFR (typically 3–5 mL/min) that is hemodynamic, not structural, and that stabilizes over time as the kidney is protected from further damage.

The KDIGO 2024 guidelines now recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for all patients with CKD and eGFR ≥ 20 mL/min/1.73m², regardless of diabetes status, albuminuria level, or underlying cause of CKD. Despite this, real-world prescription rates remain low — in part because of the specialty gap. Nephrologists may view these as endocrinology drugs; cardiologists may view them as nephrology drugs; and primary care providers may feel uncertain about initiating them. The result is therapeutic inertia at a time when the evidence for action has never been stronger.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Beyond Glucose and Weight

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have emerged as a second pillar of cardiometabolic kidney protection. While their cardiovascular benefits have been recognized since the LEADER and SUSTAIN-6 trials, dedicated kidney evidence arrived with the FLOW trial in 2024.

FLOW enrolled over 3,500 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (eGFR 25–75, UACR 300–5,000 mg/g in most). Semaglutide 1.0 mg weekly reduced the primary composite kidney outcome by 24% and significantly reduced cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality. The trial was stopped early because the evidence of benefit was so clear that continuing placebo would have been unethical.

The mechanisms of GLP-1 RA kidney protection are complementary to SGLT2 inhibitors. GLP-1 RAs improve glycemic control, promote weight loss, reduce blood pressure, and appear to have direct anti-inflammatory effects on the kidney tubules. There is also evidence suggesting they reduce oxidative stress and suppress pathways of renal fibrosis.

Importantly, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs work through different mechanisms, raising the possibility that combination therapy may offer additive or synergistic kidney and cardiovascular protection. While dedicated trials of this combination in CKD are ongoing, the pharmacologic rationale is strong, and many expert clinicians are already using both agents in appropriate patients.

Finerenone: A New Pillar of Cardiorenal Protection

Finerenone is a nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) that represents a fundamentally different approach from the older steroidal MRAs (spironolactone, eplerenone). While spironolactone and eplerenone block the mineralocorticoid receptor in a relatively blunt fashion, finerenone is more selective and has a different tissue distribution — with more balanced effects on the heart and kidney and, critically, less risk of hyperkalemia.

The FIDELIO-DKD trial enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (mostly with eGFR 25–75 and UACR 30–300 or higher). Finerenone reduced the primary composite kidney outcome by 18%. The FIGARO-DKD trial enrolled a broader population with less advanced CKD and demonstrated a 13% reduction in the primary cardiovascular composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or heart failure hospitalization.

The FIDELITY pooled analysis combined both trials (over 13,000 patients) and confirmed statistically significant reductions in both kidney and cardiovascular composite endpoints. This makes finerenone the first agent specifically shown to reduce both kidney disease progression and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic kidney disease.

Finerenone is currently indicated for patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD with albuminuria who are already on maximally tolerated RAS inhibition. It can be used in combination with SGLT2 inhibitors. Despite this evidence, finerenone remains underutilized, largely because it falls into the same specialty gap: cardiologists are unfamiliar with it because it was studied in CKD populations; nephrologists may hesitate because its primary benefit in FIGARO was cardiovascular.

Blood Pressure Management in CKD

Hypertension is both a cause and a consequence of CKD. As kidney function declines, the ability to excrete sodium and water is impaired, expanding plasma volume and raising blood pressure. Simultaneously, the diseased kidney produces excess renin, further activating the RAAS. Arterial stiffness increases due to vascular calcification and endothelial dysfunction, raising systolic pressure. The result is resistant hypertension that feeds back to accelerate kidney damage.

The SPRINT trial demonstrated that targeting a systolic blood pressure of < 120 mmHg (versus < 140 mmHg) reduced cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in high-risk adults, including a large subgroup with CKD (eGFR 20–59). The CKD subgroup showed consistent cardiovascular benefit, though the effect on kidney-specific outcomes was less clear. Intensive blood pressure lowering was associated with a small, expected decline in eGFR that did not translate into an increase in kidney failure.

The first-line agents for blood pressure management in CKD with albuminuria are ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which reduce intraglomerular pressure and slow albuminuria progression. The KDIGO 2024 guidelines recommend maximizing RAS inhibition before adding additional antihypertensives. In patients with diabetes, CKD, and albuminuria, RAS inhibition forms the foundation upon which SGLT2 inhibitors and finerenone are added. For more on hypertension management, see Under Pressure: Hypertension.

Lipid Management in CKD: The Forgotten Conversation

The dyslipidemia of CKD is distinct from typical hyperlipidemia. As kidney function declines, patients develop a characteristic pattern: elevated triglycerides, low HDL-cholesterol, and an increase in small, dense LDL particles. LDL-cholesterol itself may appear "normal" or even low, masking a highly atherogenic lipid profile. This is why ApoB — which counts the actual number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles — may be a more accurate measure of risk than LDL-C in patients with CKD.

The SHARP trial (Study of Heart and Renal Protection) demonstrated that the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe reduced major atherosclerotic events by 17% in over 9,000 patients with CKD (including those not on dialysis). This remains the largest lipid-lowering trial in CKD and provides strong evidence for statin-based therapy in this population.

The Lipids in CKD — KDIGO Guidelines recommend statin or statin/ezetimibe therapy for all adults aged ≥ 50 with CKD (eGFR < 60) and for younger adults with CKD who have additional risk factors. The guidelines take a "fire and forget" approach, recommending treatment initiation without requiring LDL-C targets. However, many experts now argue that this approach is outdated and that ApoB-guided, treat-to-target lipid management — as advocated in the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines — is more appropriate for these high-risk patients.

Despite the evidence, lipid management in CKD patients is often inadequate. Nephrologists may not routinely check lipid panels or ApoB. Cardiologists may not recognize that a "normal" LDL-C of 95 mg/dL in a patient with CKD and albuminuria may conceal an elevated ApoB of 110 mg/dL — reflecting a particle count that warrants intensification of therapy. Lp(a), an independent and largely genetic risk factor for ASCVD, is rarely checked in CKD patients, even though elevated Lp(a) compounds an already high-risk profile. For more detailed discussion of lipid targets and ApoB, see What's Your ApoB, Follow the Leader: Lipid Guidelines, and Little Napoleon Complex: Lp(a).

The Specialty Gap: Why These Patients Fall Through the Cracks

If the evidence is so strong, why aren't patients like Maria getting the care they need?

The answer lies in the structure of modern subspecialty medicine. Cardiology and nephrology developed as separate disciplines with separate training programs, separate conferences, separate journals, and separate clinical workflows. A cardiologist evaluating Maria for chest pain will focus on her coronary anatomy, left ventricular function, and arrhythmia risk. If her creatinine is elevated, the cardiologist will note it and defer to nephrology. A nephrologist evaluating Maria for CKD will focus on her eGFR trajectory, electrolytes, and proteinuria. If her cardiovascular risk is elevated, the nephrologist may note it and defer to cardiology.

Nobody steps on anybody's toes. And nobody takes ownership of the cardiorenal-metabolic patient.

SGLT2 inhibitors illustrate this perfectly. Despite being recommended by KDIGO for all CKD patients with eGFR ≥ 20, real-world data suggest that prescription rates remain disappointingly low. A 2023 analysis of U.S. commercial claims data found that fewer than 10% of eligible CKD patients were receiving an SGLT2 inhibitor. The reasons are multifactorial: unfamiliarity, inertia, prior authorization burdens, concern about side effects (largely unwarranted at recommended eGFR thresholds), and the simple fact that no single specialty "owns" this medication.

Finerenone faces an even steeper adoption curve. It was studied in nephrology-focused trials but its cardiovascular benefit was the headline finding of FIGARO. Cardiologists have rarely encountered it. Nephrologists may hesitate because they are not accustomed to prescribing medications primarily for cardiovascular risk reduction. Endocrinologists, who might be natural prescribers given the diabetic population, are often stretched thin and may not be involved in the care of every patient with DKD.

The solution, many experts argue, is the development of integrated cardiorenal-metabolic clinics — multidisciplinary programs where cardiologists, nephrologists, endocrinologists, and primary care providers collaborate on a shared treatment plan. Some academic centers have begun to establish these clinics. But for most patients, the gap remains. For more on the specialist communication imperative, see Who Needs a Specialist.

Until the system catches up, patients must advocate for themselves. That means asking: Does my cardiologist know about my kidney disease? Does my nephrologist know about my heart risk? Am I on the medications the evidence says I should be on?

Landmark References

- Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. PubMed

- Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073–2081. PubMed

- Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–2169. PubMed

- Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):807–814. PubMed

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy (CREDENCE). N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295–2306. PubMed

- Heerspink HJL, Stefansson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease (DAPA-CKD). N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436–1446. PubMed

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease (EMPA-KIDNEY). N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117–127. PubMed

- Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, et al. Effects of semaglutide on chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes (FLOW). N Engl J Med. 2024;391(2):109–121. PubMed

- Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes (FIDELIO-DKD). N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219–2229. PubMed

- Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes (FIGARO-DKD). N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):2252–2263. PubMed

- Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(6):474–484. European Heart Journal

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. PubMed

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved). N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1451–1461. PubMed

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (DELIVER). N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1089–1098. PubMed

- Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes (SELECT). N Engl J Med. 2023;389(24):2221–2232. PubMed

- Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (SHARP). Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181–2192. PubMed

- Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148(20):1606–1635. AHA Journals

- Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R. Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(19):1527–1539. PubMed

- Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, et al. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(7 Suppl 2):S148–S153. PubMed

- Matsushita K, Coresh J, Sang Y, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(7):514–525. PubMed

CKD Stage III with albuminuria is not a spectator disease. It is an active participant in cardiovascular risk — and it should be treated as such.

Your kidneys don't just filter blood. They are a window into your vascular health. If they are damaged, your heart is likely at risk too.

The treatments exist. SGLT2 inhibitors, finerenone, GLP-1 receptor agonists, optimized RAS inhibition, and aggressive lipid management can all slow progression and reduce cardiovascular events. These are not experimental. They are evidence-based, guideline-directed therapies supported by landmark randomized controlled trials.

Don't accept "we'll just watch it." Ask why you're not on an SGLT2 inhibitor. Ask if finerenone is appropriate. Ask about your ApoB. Ask about GLP-1 receptor agonists if you have diabetes or obesity.

Your cardiologist and your nephrologist need to be on the same page. If they aren't talking to each other, you need to be the bridge. Nobody should fall through the gap.

Don't forget your beans.

CardioAdvocate helps people understand what matters — and how to speak up about it.